Datasets:

problem

stringlengths 1

7.47k

| solution

stringlengths 2

13.5k

| answer

stringlengths 0

252

⌀ | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | question_type

stringclasses 1

value | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | source

stringclasses 4

values | synthetic

bool 1

class | solution_token_len

int64 1

4.63k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In $\triangle A B C$, let $D, E, F$ be the midpoints of $B C, A C, A B$ respectively and let $G$ be the centroid of the triangle.

For each value of $\angle B A C$, how many non-similar triangles are there in which $A E G F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral?

|

Let $I$ be the intersection of $A G$ and $E F$.

Let $\delta=A I \cdot I G - F I \cdot I E$. Then

$$

A I = A D / 2, \quad I G = A D / 6, \quad F I = B C / 4 = I E

$$

Further, applying the cosine rule to triangles $A B D, A C D$ we get

$$

\begin{aligned}

A B^{2} & = B C^{2} / 4 + A D^{2} - A D \cdot B C \cdot \cos \angle B D A, \\

A C^{2} & = B C^{2} / 4 + A D^{2} + A D \cdot B C \cdot \cos \angle B D A, \\

\text { so } \quad A D^{2} & = \left(A B^{2} + A C^{2} - B C^{2} / 2\right) / 2

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

\delta & = \left(A B^{2} + A C^{2} - 2 B C^{2}\right) / 24 \\

& = \left(4 A B \cdot A C \cdot \cos \angle B A C - A B^{2} - A C^{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now $A E F G$ is a cyclic quadrilateral if and only if $\delta=0$, i.e. if and only if

$$

\begin{aligned}

\cos \angle B A C & = \left(A B^{2} + A C^{2}\right) / (4 \cdot A B \cdot A C) \\

& = (A B / A C + A C / A B) / 4

\end{aligned}

$$

5

Now $A B / A C + A C / A B \geq 2$. Hence $\cos \angle B A C \geq 1 / 2$ and so $\angle B A C \leq 60^{\circ}$.

For $\angle B A C > 60^{\circ}$ there is no triangle with the required property.

For $\angle B A C = 60^{\circ}$ there exists, within similarity, precisely one triangle (which is equilateral) having the required property.

For $\angle B A C < 60^{\circ}$ there exists, within similarity, again precisely one triangle having the required property (even though for fixed median $A E$ there are two, but one arises from the other by interchanging point $B$ with point $C$, thus proving them to be similar).

|

not found

|

Geometry

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 593

|

Consider all the triangles $A B C$ which have a fixed base $A B$ and whose altitude from $C$ is a constant $h$. For which of these triangles is the product of its altitudes a maximum?

|

Let $h_{a}$ and $h_{b}$ be the altitudes from $A$ and $B$, respectively. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

A B \cdot h \cdot A C \cdot h_{b} \cdot B C \cdot h_{a} & =8 \cdot (\text{area of } \triangle A B C)^{3} \\

& =(A B \cdot h)^{3},

\end{aligned}

$$

which is a constant. So the product $h \cdot h_{a} \cdot h_{b}$ attains its maximum when the product $A C \cdot B C$ attains its minimum.

Since

$$

\begin{aligned}

(\sin C) \cdot A C \cdot B C & =B C \cdot h_{a} \\

& =2 \cdot \text{area of } \triangle A B C

\end{aligned}

$$

which is a constant, $A C \cdot B C$ attains its minimum when $\sin C$ reaches its maximum. There are two cases:

(a) $h \leq A B / 2$. Then there exists a triangle $A B C$ which has a right angle at $C$, and for precisely such a triangle $\sin C$ attains its maximum, namely 1.

(b) $h > A B / 2$. In this case the angle at $C$ is acute and assumes its maximum when the triangle is isosceles.

Note that a solution using calculus obviously exists.

|

not found

|

Geometry

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 323

|

A triangle with sides $a, b$, and $c$ is given. Denote by $s$ the semiperimeter, that is $s=(a+b+c) / 2$. Construct a triangle with sides $s-a, s-b$, and $s-c$. This process is repeated until a triangle can no longer be constructed with the sidelengths given.

For which original triangles can this process be repeated indefinitely?

Answer: Only equilateral triangles.

|

The perimeter of each new triangle constructed by the process is $(s-a)+(s-b)+(s-c) = 3s - (a+b+c) = 3s - 2s = s$, that is, it is halved. Consider a new equivalent process in which a similar triangle with side lengths $2(s-a), 2(s-b), 2(s-c)$ is constructed, so the perimeter is kept invariant.

Suppose without loss of generality that $a \leq b \leq c$. Then $2(s-c) \leq 2(s-b) \leq 2(s-a)$, and the difference between the largest side and the smallest side changes from $c-a$ to $2(s-a) - 2(s-c) = 2(c-a)$, that is, it doubles. Therefore, if $c-a > 0$ then eventually this difference becomes larger than $a+b+c$, and it's immediate that a triangle cannot be constructed with the side lengths. Hence the only possibility is $c-a = 0 \Longrightarrow a = b = c$, and it is clear that equilateral triangles can yield an infinite process, because all generated triangles are equilateral.

|

a = b = c

|

Geometry

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 250

|

Find the total number of different integer values the function

$$

f(x)=[x]+[2 x]+\left[\frac{5 x}{3}\right]+[3 x]+[4 x]

$$

takes for real numbers \( x \) with \( 0 \leq x \leq 100 \).

Note: \([t]\) is the largest integer that does not exceed \( t \).

Answer: 734.

|

Note that, since $[x+n]=[x]+n$ for any integer $n$,

$$

f(x+3)=[x+3]+[2(x+3)]+\left[\frac{5(x+3)}{3}\right]+[3(x+3)]+[4(x+3)]=f(x)+35,

$$

one only needs to investigate the interval $[0,3)$.

The numbers in this interval at which at least one of the real numbers $x, 2 x, \frac{5 x}{3}, 3 x, 4 x$ is an integer are

- $0,1,2$ for $x$;

- $\frac{n}{2}, 0 \leq n \leq 5$ for $2 x$;

- $\frac{3 n}{5}, 0 \leq n \leq 4$ for $\frac{5 x}{3}$;

- $\frac{n}{3}, 0 \leq n \leq 8$ for $3 x$;

- $\frac{n}{4}, 0 \leq n \leq 11$ for $4 x$.

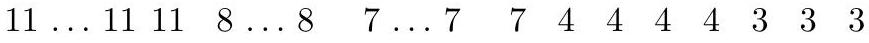

Of these numbers there are

- 3 integers $(0,1,2)$;

- 3 irreducible fractions with 2 as denominator (the numerators are $1,3,5$ );

- 6 irreducible fractions with 3 as denominator (the numerators are $1,2,4,5,7,8$ );

- 6 irreducible fractions with 4 as denominator (the numerators are $1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15$ );

- 4 irreducible fractions with 5 as denominator (the numerators are 3,6,9,12).

Therefore $f(x)$ increases 22 times per interval. Since $100=33 \cdot 3+1$, there are $33 \cdot 22$ changes of value in $[0,99)$. Finally, there are 8 more changes in [99,100]: 99, 100, $99 \frac{1}{2}, 99 \frac{1}{3}, 99 \frac{2}{3}, 99 \frac{1}{4}$, $99 \frac{3}{4}, 99 \frac{3}{5}$.

The total is then $33 \cdot 22+8=734$.

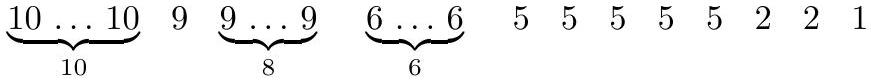

Comment: A more careful inspection shows that the range of $f$ are the numbers congruent modulo 35 to one of

$$

0,1,2,4,5,6,7,11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,23,24,25,26,28,29,30

$$

in the interval $[0, f(100)]=[0,1166]$. Since $1166 \equiv 11(\bmod 35)$, this comprises 33 cycles plus the 8 numbers in the previous list.

|

734

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 691

|

Determine all positive integers $n$ for which the equation

$$

x^{n}+(2+x)^{n}+(2-x)^{n}=0

$$

has an integer as a solution.

## Answer: $n=1$.

|

If $n$ is even, $x^{n}+(2+x)^{n}+(2-x)^{n}>0$, so $n$ is odd.

For $n=1$, the equation reduces to $x+(2+x)+(2-x)=0$, which has the unique solution $x=-4$.

For $n>1$, notice that $x$ is even, because $x, 2-x$, and $2+x$ have all the same parity. Let $x=2 y$, so the equation reduces to

$$

y^{n}+(1+y)^{n}+(1-y)^{n}=0 .

$$

Looking at this equation modulo 2 yields that $y+(1+y)+(1-y)=y+2$ is even, so $y$ is even. Using the factorization

$$

a^{n}+b^{n}=(a+b)\left(a^{n-1}-a^{n-2} b+\cdots+b^{n-1}\right) \quad \text { for } n \text { odd, }

$$

which has a sum of $n$ terms as the second factor, the equation is now equivalent to

$$

y^{n}+(1+y+1-y)\left((1+y)^{n-1}-(1+y)^{n-2}(1-y)+\cdots+(1-y)^{n-1}\right)=0

$$

or

$$

y^{n}=-2\left((1+y)^{n-1}-(1+y)^{n-2}(1-y)+\cdots+(1-y)^{n-1}\right) .

$$

Each of the $n$ terms in the second factor is odd, and $n$ is odd, so the second factor is odd. Therefore, $y^{n}$ has only one factor 2, which is a contradiction to the fact that, $y$ being even, $y^{n}$ has at least $n>1$ factors 2. Hence there are no solutions if $n>1$.

|

n=1

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 439

|

Let $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be a function such that

(i) For all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$,

$$

f(x)+f(y)+1 \geq f(x+y) \geq f(x)+f(y)

$$

(ii) For all $x \in[0,1), f(0) \geq f(x)$,

(iii) $-f(-1)=f(1)=1$.

Find all such functions $f$.

Answer: $f(x)=\lfloor x\rfloor$, the largest integer that does not exceed $x$, is the only function.

|

Plug $y \rightarrow 1$ in (i):

$$

f(x)+f(1)+1 \geq f(x+1) \geq f(x)+f(1) \Longleftrightarrow f(x)+1 \leq f(x+1) \leq f(x)+2

$$

Now plug $y \rightarrow -1$ and $x \rightarrow x+1$ in (i):

$$

f(x+1)+f(-1)+1 \geq f(x) \geq f(x+1)+f(-1) \Longleftrightarrow f(x) \leq f(x+1) \leq f(x)+1

$$

Hence $f(x+1)=f(x)+1$ and we only need to define $f(x)$ on $[0,1)$. Note that $f(1)=$ $f(0)+1 \Longrightarrow f(0)=0$.

Condition (ii) states that $f(x) \leq 0$ in $[0,1)$.

Now plug $y \rightarrow 1-x$ in (i):

$$

f(x)+f(1-x)+1 \leq f(x+(1-x)) \leq f(x)+f(1-x) \Longrightarrow f(x)+f(1-x) \geq 0

$$

If $x \in (0,1)$ then $1-x \in (0,1)$ as well, so $f(x) \leq 0$ and $f(1-x) \leq 0$, which implies $f(x)+f(1-x) \leq 0$. Thus, $f(x)=f(1-x)=0$ for $x \in (0,1)$. This combined with $f(0)=0$ and $f(x+1)=f(x)+1$ proves that $f(x)=\lfloor x \rfloor$, which satisfies the problem conditions, as since

$x+y=\lfloor x \rfloor+\lfloor y \rfloor+\{x\}+\{y\}$ and $0 \leq \{x\}+\{y\}<2 \Longrightarrow \lfloor x \rfloor+\lfloor y \rfloor \leq x+y<\lfloor x \rfloor+\lfloor y \rfloor+2$ implies

$$

\lfloor x \rfloor+\lfloor y \rfloor+1 \geq \lfloor x+y \rfloor \geq \lfloor x \rfloor+\lfloor y \rfloor.

$$

|

f(x)=\lfloor x \rfloor

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 548

|

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ with the following property: There does not exist an arithmetic progression of 1993 terms of real numbers containing exactly $n$ integers.

|

and Marking Scheme:

We first note that the integer terms of any arithmetic progression are "equally spaced", because if the $i$ th term $a_{i}$ and the $(i+j)$ th term $a_{i+j}$ of an arithmetic progression are both integers, then so is the $(i+2 j)$ th term $a_{i+2 j}=a_{i+j}+\left(a_{i+j}-a_{i}\right)$.

1 POINT for realizing that the integers must be "equally spaced".

Thus, by scaling and translation, we can assume that the integer terms of the arithmetic progression are $1,2, \cdots, n$ and we need only to consider arithmetic progression of the form

$$

1,1+\frac{1}{k}, 1+\frac{2}{k}, \cdots, 1+\frac{k-1}{k}, 2,2+\frac{1}{k}, \cdots, n-1, \cdots, n-1+\frac{k-1}{k}, n

$$

This has $k n-k+1$ terms of which exactly $n$ are integers. Moreover we can add up to $k-1$ terms on either end and get another arithmetic progression without changing the number of integer terms.

2 POINTS for noticing that the maximal sequence has an equal number of terms on either side of the integers appearing in the sequence (this includes the 1 POINT above). In other words, 2 POINTS for the scaled and translated form of the progression including the $k-1$ terms on either side.

Thus there are arithmetic progressions with $n$ integers whose length is any integer lying in the interval $[k n-k+1, k n+k-1]$, where $k$ is any positive integer. Thus we want to find the smallest $n>0$ so that, if $k$ is the largest integer satisfying $k n+k-1 \leq 1998$, then $(k+1) n-(k+1)+1 \geq 2000$.

4 POINTS for clarifying the nature of the number $n$ in this way, which includes counting the terms of the maximal and minimal sequences containing $n$ integers and bounding them accordingly (this includes the 2 POINTS above).

That is, putting $k=\lfloor 1999 /(n+1)\rfloor$, we want the smallest integer $n$ so that

$$

\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{n+1}\right\rfloor(n-1)+n \geq 2000

$$

This inequality does not hold if

$$

\frac{1999}{n+1} \cdot(n-1)+n<2000

$$

2 POINTS for setting up an inequality for $n$.

This simplifies to $n^{2}<3999$, that is, $n \leq 63$. Now we check integers from $n=64$ on:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \text { for } n=64,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{65}\right\rfloor \cdot 63+64=30 \cdot 63+64=1954<2000 ; \\

& \text { for } n=65,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{66}\right\rfloor \cdot 64+65=30 \cdot 64+65=1985<2000 ; \\

& \text { for } n=66,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{67}\right\rfloor \cdot 65+66=29 \cdot 65+66=1951<2000 ; \\

& \text { for } n=67,\left\lfloor\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{68}\right\rfloor \cdot 66+67=29 \cdot 66+67=1981<2000 ;\right. \\

& \text { for } n=68,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{69}\right\rfloor \cdot 67+68=28 \cdot 67+68=1944<2000 ; \\

& \text { for } n=69,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{70}\right\rfloor \cdot 68+69=28 \cdot 68+69=1973<2000 ; \\

& \text { for } n=70,\left\lfloor\frac{1999}{71}\right\rfloor \cdot 69+70=28 \cdot 69+70=2002 \geq 2000 .

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus the answer is $n=70$.

1 POINT for checking these numbers and finding that $n=70$.

|

70

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,126

|

Compute the sum $S=\sum_{i=0}^{101} \frac{x_{i}^{3}}{1-3 x_{i}+3 x_{i}^{2}}$ for $x_{i}=\frac{i}{101}$.

Answer: $S=51$.

|

Since $x_{101-i}=\frac{101-i}{101}=1-\frac{i}{101}=1-x_{i}$ and

$$

1-3 x_{i}+3 x_{i}^{2}=\left(1-3 x_{i}+3 x_{i}^{2}-x_{i}^{3}\right)+x_{i}^{3}=\left(1-x_{i}\right)^{3}+x_{i}^{3}=x_{101-i}^{3}+x_{i}^{3},

$$

we have, by replacing $i$ by $101-i$ in the second sum,

$$

2 S=S+S=\sum_{i=0}^{101} \frac{x_{i}^{3}}{x_{101-i}^{3}+x_{i}^{3}}+\sum_{i=0}^{101} \frac{x_{101-i}^{3}}{x_{i}^{3}+x_{101-i}^{3}}=\sum_{i=0}^{101} \frac{x_{i}^{3}+x_{101-i}^{3}}{x_{101-i}^{3}+x_{i}^{3}}=102,

$$

so $S=51$.

|

51

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 305

|

Given a permutation $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ of the sequence $0,1, \ldots, n$. A transposition of $a_{i}$ with $a_{j}$ is called legal if $a_{i}=0$ for $i>0$, and $a_{i-1}+1=a_{j}$. The permutation $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ is called regular if after a number of legal transpositions it becomes $(1,2, \ldots, n, 0)$. For which numbers $n$ is the permutation $(1, n, n-1, \ldots, 3,2,0)$ regular?

Answer: $n=2$ and $n=2^{k}-1, k$ positive integer.

|

A legal transposition consists of looking at the number immediately before 0 and exchanging 0 and its successor; therefore, we can perform at most one legal transposition to any permutation, and a legal transposition is not possible only and if only 0 is preceded by \( n \).

If \( n=1 \) or \( n=2 \) there is nothing to do, so \( n=1=2^{1}-1 \) and \( n=2 \) are solutions. Suppose that \( n>3 \) in the following.

Call a pass a maximal sequence of legal transpositions that move 0 to the left. We first illustrate what happens in the case \( n=15 \), which is large enough to visualize what is going on. The first pass is

\[

\begin{aligned}

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,0) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,5,4,0,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,0,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,0,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,0,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,0,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,0,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,0,14,15,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3)

\end{aligned}

\]

After exchanging 0 and 2, the second pass is

\[

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,14,15,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,0,3) \\

& (1,2,14,15,12,13, \mathbf{1 0}, 11,8,9,0,7,4,5,6,3) \\

& (1,2, \mathbf{1 4}, 15,12,13,0,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,3) \\

& (1,2,0,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,3)

\end{aligned}

\]

After exchanging 0 and 3, the third pass is

\[

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,0) \\

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,0,4,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,0,8,9,10,11,4,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,0,12,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,4,5,6,7)

\end{aligned}

\]

After exchanging 0 and 4, the fourth pass is

\[

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,3,4,12,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,0,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,4,0,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,12,5,6,7)

\end{aligned}

\]

And then one can successively perform the operations to eventually find

\[

(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,0,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15)

\]

after which 0 will move one unit to the right with each transposition, and \( n=15 \) is a solution. The general case follows.

Case 1: \( n>2 \) even: After the first pass, in which 0 is transposed successively with \( 3,5, \ldots, n-1 \), after which 0 is right after \( n \), and no other legal transposition can be performed. So \( n \) is not a solution in this case.

Case 2: \( n=2^{k}-1 \) : Denote \( N=n+1, R=2^{r},[a: b]=(a, a+1, a+2, \ldots, b) \), and concatenation by a comma. Let \( P_{r} \) be the permutation

\[

[1: R-1],(0),[N-R: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R-1], \ldots,[2 R: 3 R-1],[R: 2 R-1]

\]

\( P_{r} \) is formed by the blocks \( [1: R-1],(0) \), and other \( 2^{k-r}-1 \) blocks of size \( R=2^{r} \) with consecutive numbers, beginning with \( t R \) and finishing with \( (t+1) R-1 \), in decreasing order of \( t \). Also define \( P_{0} \) as the initial permutation.

Then it can be verified that \( P_{r+1} \) is obtained from \( P_{r} \) after a number of legal transpositions: it can be easily verified that \( P_{0} \) leads to \( P_{1} \), as 0 is transposed successively with \( 3,5, \ldots, n-1 \), shifting cyclically all numbers with even indices; this is \( P_{1} \).

Starting from \( P_{r}, r>0 \), 0 is successively transposed with \( R, 3 R, \ldots, N-R \). The numbers \( 0, N-R, N-3 R, \ldots, 3 R, R \) are cyclically shifted. This means that \( R \) precedes 0, and the blocks become

\[

\begin{gathered}

{[1: R],(0),[N-R+1: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R],[N-3 R+1: N-2 R-1], \ldots,} \\

{[3 R+1: 4 R-1],[2 R: 3 R],[R+1: 2 R-1]}

\end{gathered}

\]

Note that the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number.

Now \( 0, N-R+1, N-3 R+1, \ldots, 3 R+1, R+1 \) are shifted. Note that, for every \( i \)th block, \( i \) odd greater than 1, the first number is cyclically shifted, and the blocks become

\[

\begin{gathered}

{[1: R+1],(0),[N-R+2: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R+1],[N-3 R+2: N-2 R-1], \ldots,} \\

{[3 R+1: 4 R-1],[2 R: 3 R+1],[R+2: 2 R-1]}

\end{gathered}

\]

The same phenomenon happened: the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number. This pattern continues: \( 0, N-R+u, N-3 R+u, \ldots, R+u \) are shifted, \( u=0,1,2, \ldots, R-1 \), the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number, until they vanish. We finish with

\[

[1: 2 R-1],(0),[N-2 R: N-1], \ldots,[2 R: 4 R-1]

\]

which is precisely \( P_{r+1} \).

Since \( P_{k}=[1: N-1],(0), n=2^{k}-1 \) is a solution.

Case 3: \( n \) is odd, but is not of the form \( 2^{k}-1 \). Write \( n+1 \) as \( n+1=2^{a}(2 b+1), b \geq 1 \), and define \( P_{0}, \ldots, P_{a} \) as in the previous case. Since \( 2^{a} \) divides \( N=n+1 \), the same rules apply, and we obtain \( P_{a} \):

\[

\left[1: 2^{a}-1\right],(0),\left[N-2^{a}: N-1\right],\left[N-2^{a+1}: N-2^{a}-1\right], \ldots,\left[2^{a+1}: 3 \cdot 2^{a}-1\right],\left[2^{a}: 2^{a+1}-1\right]

\]

But then 0 is transposed with \( 2^{a}, 3 \cdot 2^{a}, \ldots,(2 b-1) \cdot 2^{a}=N-2^{a+1} \), after which 0 is put immediately after \( N-1=n \), and cannot be transposed again. Therefore, \( n \) is not a solution. All cases were studied, and so we are done.

Comment: The general problem of finding the number of regular permutations for any \( n \) seems to be difficult. A computer finds the first few values

\[

1,2,5,14,47,189,891,4815,29547

\]

which is not catalogued at oeis.org.

|

n=2 \text{ and } n=2^{k}-1, k \text{ positive integer}

|

Combinatorics

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 2,430

|

Determine all finite nonempty sets $S$ of positive integers satisfying

$$

\frac{i+j}{(i, j)} \text { is an element of } S \text { for all } i, j \text { in } S \text {, }

$$

where $(i, j)$ is the greatest common divisor of $i$ and $j$.

Answer: $S=\{2\}$.

|

Let $k \in S$. Then $\frac{k+k}{(k, k)}=2$ is in $S$ as well.

Suppose for the sake of contradiction that there is an odd number in $S$, and let $k$ be the largest such odd number. Since $(k, 2)=1, \frac{k+2}{(k, 2)}=k+2>k$ is in $S$ as well, a contradiction. Hence $S$ has no odd numbers.

Now suppose that $\ell>2$ is the second smallest number in $S$. Then $\ell$ is even and $\frac{\ell+2}{(\ell, 2)}=\frac{\ell}{2}+1$ is in $S$. Since $\ell>2 \Longrightarrow \frac{\ell}{2}+1>2, \frac{\ell}{2}+1 \geq \ell \Longleftrightarrow \ell \leq 2$, a contradiction again.

Therefore $S$ can only contain 2, and $S=\{2\}$ is the only solution.

|

S=\{2\}

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 228

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. Find the largest nonnegative real number $f(n)$ (depending on $n$) with the following property: whenever $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ are real numbers such that $a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}$ is an integer, there exists some $i$ such that $\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right| \geq f(n)$.

|

The answer is

$$

f(n)=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

0 & \text { if } n \text { is even, } \\

\frac{1}{2 n} & \text { if } n \text { is odd. }

\end{array}\right.

$$

First, assume that $n$ is even. If $a_{i}=\frac{1}{2}$ for all $i$, then the sum $a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}$ is an integer. Since $\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right|=0$ for all $i$, we may conclude $f(n)=0$ for any even $n$.

Now assume that $n$ is odd. Suppose that $\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right|<\frac{1}{2 n}$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n$. Then, since $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}$ is an integer,

$$

\frac{1}{2} \leq\left|\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}-\frac{n}{2}\right| \leq \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right|<\frac{1}{2 n} \cdot n=\frac{1}{2}

$$

a contradiction. Thus $\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right| \geq \frac{1}{2 n}$ for some $i$, as required. On the other hand, putting $n=2 m+1$ and $a_{i}=\frac{m}{2 m+1}$ for all $i$ gives $\sum a_{i}=m$, while

$$

\left|a_{i}-\frac{1}{2}\right|=\frac{1}{2}-\frac{m}{2 m+1}=\frac{1}{2(2 m+1)}=\frac{1}{2 n}

$$

for all $i$. Therefore, $f(n)=\frac{1}{2 n}$ is the best possible for any odd $n$.

|

f(n)=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

0 & \text { if } n \text { is even, } \\

\frac{1}{2 n} & \text { if } n \text { is odd. }

\end{array}\right.}

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 484

|

Consider the function $f: \mathbb{N}_{0} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}_{0}$, where $\mathbb{N}_{0}$ is the set of all non-negative integers, defined by the following conditions:

(i) $f(0)=0$,

(ii) $f(2 n)=2 f(n)$ and

(iii) $f(2 n+1)=n+2 f(n)$ for all $n \geq 0$.

(a) Determine the three sets $L:=\{n \mid f(n)f(n+1)\}$.

(b) For each $k \geq 0$, find a formula for $a_{k}:=\max \left\{f(n): 0 \leq n \leq 2^{k}\right\}$ in terms of $k$.

|

(a) Let

$$

L_{1}:=\{2 k: k>0\}, \quad E_{1}:=\{0\} \cup\{4 k+1: k \geq 0\}, \quad \text { and } G_{1}:=\{4 k+3: k \geq 0\} .

$$

We will show that $L_{1}=L, E_{1}=E$, and $G_{1}=G$. It suffices to verify that $L_{1} \subseteq E, E_{1} \subseteq E$, and $G_{1} \subseteq G$ because $L_{1}, E_{1}$, and $G_{1}$ are mutually disjoint and $L_{1} \cup E_{1} \cup G_{1}=\mathbb{N}_{0}$.

Firstly, if $k>0$, then $f(2 k)-f(2 k+1)=-k<0$ and therefore $L_{1} \subseteq L$.

Secondly, $f(0)=0$ and

$$

\begin{aligned}

& f(4 k+1)=2 k+2 f(2 k)=2 k+4 f(k) \\

& f(4 k+2)=2 f(2 k+1)=2(k+2 f(k))=2 k+4 f(k)

\end{aligned}

$$

for all $k \geq 0$. Thus, $E_{1} \subseteq E$.

Lastly, in order to prove $G_{1} \subset G$, we claim that $f(n+1)-f(n) \leq n$ for all $n$. (In fact, one can prove a stronger inequality : $f(n+1)-f(n) \leq n / 2$.) This is clearly true for even $n$ from the definition since for $n=2 t$,

$$

f(2 t+1)-f(2 t)=t \leq n

$$

If $n=2 t+1$ is odd, then (assuming inductively that the result holds for all nonnegative $m<n$ ), we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(n+1)-f(n) & =f(2 t+2)-f(2 t+1)=2 f(t+1)-t-2 f(t) \\

& =2(f(t+1)-f(t))-t \leq 2 t-t=t<n .

\end{aligned}

$$

For all $k \geq 0$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

& f(4 k+4)-f(4 k+3)=f(2(2 k+2))-f(2(2 k+1)+1) \\

& =4 f(k+1)-(2 k+1+2 f(2 k+1))=4 f(k+1)-(2 k+1+2 k+4 f(k)) \\

& =4(f(k+1)-f(k))-(4 k+1) \leq 4 k-(4 k+1)<0 .

\end{aligned}

$$

This proves $G_{1} \subseteq G$.

(b) Note that $a_{0}=a_{1}=f(1)=0$. Let $k \geq 2$ and let $N_{k}=\left\{0,1,2, \ldots, 2^{k}\right\}$. First we claim that the maximum $a_{k}$ occurs at the largest number in $G \cap N_{k}$, that is, $a_{k}=f\left(2^{k}-1\right)$. We use mathematical induction on $k$ to prove the claim. Note that $a_{2}=f(3)=f\left(2^{2}-1\right)$.

Now let $k \geq 3$. For every even number $2 t$ with $2^{k-1}+1<2 t \leq 2^{k}$,

$$

f(2 t)=2 f(t) \leq 2 a_{k-1}=2 f\left(2^{k-1}-1\right)

$$

by induction hypothesis. For every odd number $2 t+1$ with $2^{k-1}+1 \leq 2 t+1<2^{k}$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(2 t+1) & =t+2 f(t) \leq 2^{k-1}-1+2 f(t) \\

& \leq 2^{k-1}-1+2 a_{k-1}=2^{k-1}-1+2 f\left(2^{k-1}-1\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

again by induction hypothesis. Combining ( $\dagger$ ), ( $\ddagger$ ) and

$$

f\left(2^{k}-1\right)=f\left(2\left(2^{k-1}-1\right)+1\right)=2^{k-1}-1+2 f\left(2^{k-1}-1\right)

$$

we may conclude that $a_{k}=f\left(2^{k}-1\right)$ as desired.

Furthermore, we obtain

$$

a_{k}=2 a_{k-1}+2^{k-1}-1

$$

for all $k \geq 3$. Note that this recursive formula for $a_{k}$ also holds for $k \geq 0,1$ and 2 . Unwinding this recursive formula, we finally get

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{k} & =2 a_{k-1}+2^{k-1}-1=2\left(2 a_{k-2}+2^{k-2}-1\right)+2^{k-1}-1 \\

& =2^{2} a_{k-2}+2 \cdot 2^{k-1}-2-1=2^{2}\left(2 a_{k-3}+2^{k-3}-1\right)+2 \cdot 2^{k-1}-2-1 \\

& =2^{3} a_{k-3}+3 \cdot 2^{k-1}-2^{2}-2-1 \\

& \vdots \\

& =2^{k} a_{0}+k 2^{k-1}-2^{k-1}-2^{k-2}-\ldots-2-1 \\

& =k 2^{k-1}-2^{k}+1 \quad \text { for all } k \geq 0 .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

a_{k} = k 2^{k-1} - 2^{k} + 1

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,458

|

Let \(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, a_{5}\) be real numbers satisfying the following equations:

$$

\frac{a_{1}}{k^{2}+1}+\frac{a_{2}}{k^{2}+2}+\frac{a_{3}}{k^{2}+3}+\frac{a_{4}}{k^{2}+4}+\frac{a_{5}}{k^{2}+5}=\frac{1}{k^{2}} \text { for } k=1,2,3,4,5

$$

Find the value of \(\frac{a_{1}}{37}+\frac{a_{2}}{38}+\frac{a_{3}}{39}+\frac{a_{4}}{40}+\frac{a_{5}}{41}\). (Express the value in a single fraction.)

|

Let $R(x):=\frac{a_{1}}{x^{2}+1}+\frac{a_{2}}{x^{2}+2}+\frac{a_{3}}{x^{2}+3}+\frac{a_{4}}{x^{2}+4}+\frac{a_{5}}{x^{2}+5}$. Then $R( \pm 1)=1$, $R( \pm 2)=\frac{1}{4}, R( \pm 3)=\frac{1}{9}, R( \pm 4)=\frac{1}{16}, R( \pm 5)=\frac{1}{25}$ and $R(6)$ is the value to be found. Let's put $P(x):=\left(x^{2}+1\right)\left(x^{2}+2\right)\left(x^{2}+3\right)\left(x^{2}+4\right)\left(x^{2}+5\right)$ and $Q(x):=R(x) P(x)$. Then for $k= \pm 1, \pm 2, \pm 3, \pm 4, \pm 5$, we get $Q(k)=R(k) P(k)=\frac{P(k)}{k^{2}}$, that is, $P(k)-k^{2} Q(k)=0$. Since $P(x)-x^{2} Q(x)$ is a polynomial of degree 10 with roots $\pm 1, \pm 2, \pm 3, \pm 4, \pm 5$, we get

$$

P(x)-x^{2} Q(x)=A\left(x^{2}-1\right)\left(x^{2}-4\right)\left(x^{2}-9\right)\left(x^{2}-16\right)\left(x^{2}-25\right)

$$

Putting $x=0$, we get $A=\frac{P(0)}{(-1)(-4)(-9)(-16)(-25)}=-\frac{1}{120}$. Finally, dividing both sides of $(*)$ by $P(x)$ yields

$$

1-x^{2} R(x)=1-x^{2} \frac{Q(x)}{P(x)}=-\frac{1}{120} \cdot \frac{\left(x^{2}-1\right)\left(x^{2}-4\right)\left(x^{2}-9\right)\left(x^{2}-16\right)\left(x^{2}-25\right)}{\left(x^{2}+1\right)\left(x^{2}+2\right)\left(x^{2}+3\right)\left(x^{2}+4\right)\left(x^{2}+5\right)}

$$

and hence that

$$

1-36 R(6)=-\frac{35 \times 32 \times 27 \times 20 \times 11}{120 \times 37 \times 38 \times 39 \times 40 \times 41}=-\frac{3 \times 7 \times 11}{13 \times 19 \times 37 \times 41}=-\frac{231}{374699}

$$

which implies $R(6)=\frac{187465}{6744582}$.

Remark. We can get $a_{1}=\frac{1105}{72}, a_{2}=-\frac{2673}{40}, a_{3}=\frac{1862}{15}, a_{4}=-\frac{1885}{18}, a_{5}=\frac{1323}{40}$ by solving the given system of linear equations, which is extremely messy and takes a lot of time.

|

\frac{187465}{6744582}

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 869

|

A sequence of real numbers $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots$ is said to be good if the following three conditions hold.

(i) The value of $a_{0}$ is a positive integer.

(ii) For each non-negative integer $i$ we have $a_{i+1}=2 a_{i}+1$ or $a_{i+1}=\frac{a_{i}}{a_{i}+2}$.

(iii) There exists a positive integer $k$ such that $a_{k}=2014$.

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ such that there exists a good sequence $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots$ of real numbers with the property that $a_{n}=2014$.

Answer: 60.

|

Note that

$$

a_{i+1}+1=2\left(a_{i}+1\right) \text { or } a_{i+1}+1=\frac{a_{i}+a_{i}+2}{a_{i}+2}=\frac{2\left(a_{i}+1\right)}{a_{i}+2} .

$$

Hence

$$

\frac{1}{a_{i+1}+1}=\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{a_{i}+1} \text { or } \frac{1}{a_{i+1}+1}=\frac{a_{i}+2}{2\left(a_{i}+1\right)}=\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{a_{i}+1}+\frac{1}{2} .

$$

Therefore,

$$

\frac{1}{a_{k}+1}=\frac{1}{2^{k}} \cdot \frac{1}{a_{0}+1}+\sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{\varepsilon_{i}}{2^{k-i+1}}

$$

where $\varepsilon_{i}=0$ or 1. Multiplying both sides by $2^{k}\left(a_{k}+1\right)$ and putting $a_{k}=2014$, we get

$$

2^{k}=\frac{2015}{a_{0}+1}+2015 \cdot\left(\sum_{i=1}^{k} \varepsilon_{i} \cdot 2^{i-1}\right)

$$

where $\varepsilon_{i}=0$ or 1. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(2,2015)=1$, we have $a_{0}+1=2015$ and $a_{0}=2014$. Therefore,

$$

2^{k}-1=2015 \cdot\left(\sum_{i=1}^{k} \varepsilon_{i} \cdot 2^{i-1}\right)

$$

where $\varepsilon_{i}=0$ or 1. We now need to find the smallest $k$ such that $2015 \mid 2^{k}-1$. Since $2015=$ $5 \cdot 13 \cdot 31$, from the Fermat little theorem we obtain $5\left|2^{4}-1,13\right| 2^{12}-1$ and $31 \mid 2^{30}-1$. We also have $\operatorname{lcm}[4,12,30]=60$, hence $5\left|2^{60}-1,13\right| 2^{60}-1$ and $31 \mid 2^{60}-1$, which gives $2015 \mid 2^{60}-1$.

But $5 \nmid 2^{30}-1$ and so $k=60$ is the smallest positive integer such that $2015 \mid 2^{k}-1$. To conclude, the smallest positive integer $k$ such that $a_{k}=2014$ is when $k=60$.

Alternative solution 1. Clearly all members of the sequence are positive rational numbers. For each positive integer $i$, we have $a_{i}=\frac{a_{i+1}-1}{2}$ or $a_{i}=\frac{2 a_{i+1}}{1-a_{i+1}}$. Since $a_{i}>0$ we deduce that

$$

a_{i}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

\frac{a_{i+1}-1}{2} & \text { if } a_{i+1}>1 \\

\frac{2 a_{i+1}}{1-a_{i+1}} & \text { if } a_{i+1}<1

\end{array}\right.

$$

Let $a_{i}=\frac{m_{i}}{n_{i}}$ where $m_{i}, n_{i} \in \mathbb{N}^{+}$ and $\operatorname{gcd}\left(m_{i}, n_{i}\right)=1$. Then

$$

\left(m_{i+1}, n_{i+1}\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

\left(m_{i}+n_{i}, 2 n_{i}\right) & \text { if } m_{i}>n_{i} \\ \left(2 m_{i}, n_{i}-m_{i}\right) & \text { if } m_{i}<n_{i}

\end{array}\right.

$$

Easy inductions show that $m_{i}+n_{i}=2015,1 \leq m_{i}, n_{i} \leq 2014$ and $\operatorname{gcd}\left(m_{i}, n_{i}\right)=1$ for $i \geq 0$. Since $a_{0} \in \mathbb{N}^{+}$ and $\operatorname{gcd}\left(m_{k}, n_{k}\right)=1$, we require $n_{k}=1$. An easy induction shows that $\left(m_{i}, n_{i}\right) \equiv\left(-2^{i}, 2^{i}\right)(\bmod 2015)$ for $i=0,1, \ldots, k$.

Thus $2^{k} \equiv 1(\bmod 2015)$. As in the official solution, the smallest such $k$ is $k=60$. This yields $n_{k} \equiv 1(\bmod 2015)$. But since $1 \leq n_{k}, m_{k} \leq 2014$, it follows that $a_{0}$ is an integer.

|

60

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,337

|

A positive integer is called fancy if it can be expressed in the form

$$

2^{a_{1}}+2^{a_{2}}+\cdots+2^{a_{100}}

$$

where $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{100}$ are non-negative integers that are not necessarily distinct.

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ such that no multiple of $n$ is a fancy number.

Answer: The answer is $n=2^{101}-1$.

Translate the above text into English, please keep the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

The text provided is already in English, so no translation is needed. Here is the text as requested:

A positive integer is called fancy if it can be expressed in the form

$$

2^{a_{1}}+2^{a_{2}}+\cdots+2^{a_{100}}

$$

where $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{100}$ are non-negative integers that are not necessarily distinct.

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ such that no multiple of $n$ is a fancy number.

Answer: The answer is $n=2^{101}-1$.

|

Let $k$ be any positive integer less than $2^{101}-1$. Then $k$ can be expressed in binary notation using at most 100 ones, and therefore there exists a positive integer $r$ and non-negative integers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{r}$ such that $r \leq 100$ and $k=2^{a_{1}}+\cdots+2^{a_{r}}$. Notice that for a positive integer $s$ we have:

$$

\begin{aligned}

2^{s} k & =2^{a_{1}+s}+2^{a_{2}+s}+\cdots+2^{a_{r-1}+s}+\left(1+1+2+\cdots+2^{s-1}\right) 2^{a_{r}} \\

& =2^{a_{1}+s}+2^{a_{2}+s}+\cdots+2^{a_{r-1}+s}+2^{a_{r}}+2^{a_{r}}+\cdots+2^{a_{r}+s-1} .

\end{aligned}

$$

This shows that $k$ has a multiple that is a sum of $r+s$ powers of two. In particular, we may take $s=100-r \geq 0$, which shows that $k$ has a multiple that is a fancy number.

We will now prove that no multiple of $n=2^{101}-1$ is a fancy number. In fact we will prove a stronger statement, namely, that no multiple of $n$ can be expressed as the sum of at most 100 powers of 2.

For the sake of contradiction, suppose that there exists a positive integer $c$ such that $c n$ is the sum of at most 100 powers of 2. We may assume that $c$ is the smallest such integer. By repeatedly merging equal powers of two in the representation of $c n$ we may assume that

$$

c n=2^{a_{1}}+2^{a_{2}}+\cdots+2^{a_{r}}

$$

where $r \leq 100$ and $a_{1}<a_{2}<\ldots<a_{r}$ are distinct non-negative integers. Consider the following two cases:

- If $a_{r} \geq 101$, then $2^{a_{r}}-2^{a_{r}-101}=2^{a_{r}-101} n$. It follows that $2^{a_{1}}+2^{a_{2}}+\cdots+2^{a_{r}-1}+2^{a_{r}-101}$ would be a multiple of $n$ that is smaller than $c n$. This contradicts the minimality of $c$.

- If $a_{r} \leq 100$, then $\left\{a_{1}, \ldots, a_{r}\right\}$ is a proper subset of $\{0,1, \ldots, 100\}$. Then

$$

n \leq c n<2^{0}+2^{1}+\cdots+2^{100}=n

$$

This is also a contradiction.

From these contradictions we conclude that it is impossible for $c n$ to be the sum of at most 100 powers of 2. In particular, no multiple of $n$ is a fancy number.

|

2^{101}-1

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 773

|

We call a 5-tuple of integers arrangeable if its elements can be labeled $a$, $b, c, d, e$ in some order so that $a-b+c-d+e=29$. Determine all 2017-tuples of integers $n_{1}, n_{2}, \ldots, n_{2017}$ such that if we place them in a circle in clockwise order, then any 5 -tuple of numbers in consecutive positions on the circle is arrangeable.

Answer: $n_{1}=\cdots=n_{2017}=29$.

|

A valid 2017-tuple is \( n_{1} = \cdots = n_{2017} = 29 \). We will show that it is the only solution.

We first replace each number \( n_{i} \) in the circle by \( m_{i} := n_{i} - 29 \). Since the condition \( a - b + c - d + e = 29 \) can be rewritten as \( (a - 29) - (b - 29) + (c - 29) - (d - 29) + (e - 29) = 0 \), we have that any five consecutive replaced integers in the circle can be labeled \( a, b, c, d, e \) in such a way that \( a - b + c - d + e = 0 \). We claim that this is possible only when all of the \( m_{i} \)'s are 0 (and thus all of the original \( n_{i} \)'s are 29).

We work with indexes modulo 2017. Notice that for every \( i \), \( m_{i} \) and \( m_{i+5} \) have the same parity. Indeed, this follows from \( m_{i} \equiv m_{i+1} + m_{i+2} + m_{i+3} + m_{i+4} \equiv m_{i+5} \pmod{2} \). Since \( \gcd(5, 2017) = 1 \), this implies that all \( m_{i} \)'s are of the same parity. Since \( m_{1} + m_{2} + m_{3} + m_{4} + m_{5} \) is even, all \( m_{i} \)'s must be even as well.

Suppose for the sake of contradiction that not all \( m_{i} \)'s are zero. Then our condition still holds when we divide each number in the circle by 2. However, by performing repeated divisions, we eventually reach a point where some \( m_{i} \) is odd. This is a contradiction.

|

n_{1} = \cdots = n_{2017} = 29

|

Combinatorics

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 476

|

Determine all the functions $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that

$$

f\left(x^{2}+f(y)\right)=f(f(x))+f\left(y^{2}\right)+2 f(x y)

$$

for all real number $x$ and $y$.

Answer: The possible functions are $f(x)=0$ for all $x$ and $f(x)=x^{2}$ for all $x$.

|

By substituting \(x=y=0\) in the given equation of the problem, we obtain that \(f(0)=0\). Also, by substituting \(y=0\), we get \(f\left(x^{2}\right)=f(f(x))\) for any \(x\).

Furthermore, by letting \(y=1\) and simplifying, we get

\[

2 f(x)=f\left(x^{2}+f(1)\right)-f\left(x^{2}\right)-f(1)

\]

from which it follows that \(f(-x)=f(x)\) must hold for every \(x\).

Suppose now that \(f(a)=f(b)\) holds for some pair of numbers \(a, b\). Then, by letting \(y=a\) and \(y=b\) in the given equation, comparing the two resulting identities and using the fact that \(f\left(a^{2}\right)=f(f(a))=f(f(b))=f\left(b^{2}\right)\) also holds under the assumption, we get the fact that

\[

f(a)=f(b) \Rightarrow f(a x)=f(b x) \quad \text { for any real number } x

\]

Consequently, if for some \(a \neq 0, f(a)=0\), then we see that, for any \(x, f(x)=f\left(a \cdot \frac{x}{a}\right) = f\left(0 \cdot \frac{x}{a}\right) = f(0) = 0\), which gives a trivial solution to the problem.

In the sequel, we shall try to find a non-trivial solution for the problem. So, let us assume from now on that if \(a \neq 0\) then \(f(a) \neq 0\) must hold. We first note that since \(f(f(x))=f\left(x^{2}\right)\) for all \(x\), the right-hand side of the given equation equals \(f\left(x^{2}\right)+f\left(y^{2}\right)+2 f(x y)\), which is invariant if we interchange \(x\) and \(y\). Therefore, we have

\[

f\left(x^{2}\right)+f\left(y^{2}\right)+2 f(x y)=f\left(x^{2}+f(y)\right)=f\left(y^{2}+f(x)\right) \quad \text { for every pair } x, y

\]

Next, let us show that for any \(x, f(x) \geq 0\) must hold. Suppose, on the contrary, \(f(s)=-t^{2}\) holds for some pair \(s, t\) of non-zero real numbers. By setting \(x=s, y=t\) in the right hand side of (2), we get \(f\left(s^{2}+f(t)\right)=f\left(t^{2}+f(s)\right)=f(0)=0\), so \(f(t)=-s^{2}\). We also have \(f\left(t^{2}\right)=f\left(-t^{2}\right)=f(f(s))=f\left(s^{2}\right)\). By applying (2) with \(x=\sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\) and \(y=s\), we obtain

\[

f\left(s^{2}+t^{2}\right)+2 f\left(s \cdot \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\right)=0

\]

and similarly, by applying (2) with \(x=\sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\) and \(y=t\), we obtain

\[

f\left(s^{2}+t^{2}\right)+2 f\left(t \cdot \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\right)=0

\]

Consequently, we obtain

\[

f\left(s \cdot \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\right)=f\left(t \cdot \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\right)

\]

By applying (1) with \(a=s \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}, b=t \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\) and \(x=1 / \sqrt{s^{2}+t^{2}}\), we obtain \(f(s) = f(t) = -s^{2}\), from which it follows that

\[

0=f\left(s^{2}+f(s)\right)=f\left(s^{2}\right)+f\left(s^{2}\right)+2 f\left(s^{2}\right)=4 f\left(s^{2}\right)

\]

a contradiction to the fact \(s^{2}>0\). Thus we conclude that for all \(x \neq 0, f(x)>0\) must be satisfied.

Now, we show the following fact

\[

k>0, f(k)=1 \Leftrightarrow k=1

\]

Let \(k>0\) for which \(f(k)=1\). We have \(f\left(k^{2}\right)=f(f(k))=f(1)\), so by (1), \(f(1 / k)=f(k) = 1\), so we may assume \(k \geq 1\). By applying (2) with \(x=\sqrt{k^{2}-1}\) and \(y=k\), and using \(f(x) \geq 0\), we get

\[

f\left(k^{2}-1+f(k)\right)=f\left(k^{2}-1\right)+f\left(k^{2}\right)+2 f\left(k \sqrt{k^{2}-1}\right) \geq f\left(k^{2}-1\right)+f\left(k^{2}\right).

\]

This simplifies to \(0 \geq f\left(k^{2}-1\right) \geq 0\), so \(k^{2}-1=0\) and thus \(k=1\).

Next we focus on showing \(f(1)=1\). If \(f(1)=m \leq 1\), then we may proceed as above by setting \(x=\sqrt{1-m}\) and \(y=1\) to get \(m=1\). If \(f(1)=m \geq 1\), now we note that \(f(m)=f(f(1))=f\left(1^{2}\right)=f(1)=m \leq m^{2}\). We may then proceed as above with \(x=\sqrt{m^{2}-m}\) and \(y=1\) to show \(m^{2}=m\) and thus \(m=1\).

We are now ready to finish. Let \(x>0\) and \(m=f(x)\). Since \(f(f(x))=f\left(x^{2}\right)\), then \(f\left(x^{2}\right) = f(m)\). But by (1), \(f\left(m / x^{2}\right)=1\). Therefore \(m=x^{2}\). For \(x<0\), we have \(f(x)=f(-x)=f\left(x^{2}\right)\) as well. Therefore, for all \(x, f(x)=x^{2}\).

|

f(x)=0 \text{ or } f(x)=x^2

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,592

|

Determine all positive integers $k$ for which there exist a positive integer $m$ and a set $S$ of positive integers such that any integer $n>m$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ in exactly $k$ ways.

|

We claim that $k=2^{a}$ for all $a \geq 0$.

Let $A=\{1,2,4,8, \ldots\}$ and $B=\mathbb{N} \backslash A$. For any set $T$, let $s(T)$ denote the sum of the elements of $T$. (If $T$ is empty, we let $s(T)=0$.)

We first show that any positive integer $k=2^{a}$ satisfies the desired property. Let $B^{\prime}$ be a subset of $B$ with $a$ elements, and let $S=A \cup B^{\prime}$. Recall that any nonnegative integer has a unique binary representation. Hence, for any integer $t>s\left(B^{\prime}\right)$ and any subset $B^{\prime \prime} \subseteq B^{\prime}$, the number $t-s\left(B^{\prime \prime}\right)$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $A$ in a unique way. This means that $t$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $B^{\prime}$ in exactly $2^{a}$ ways.

Next, assume that some positive integer $k$ satisfies the desired property for a positive integer $m \geq 2$ and a set $S$. Clearly, $S$ is infinite.

Lemma: For all sufficiently large $x \in S$, the smallest element of $S$ larger than $x$ is $2 x$.

Proof of Lemma: Let $x \in S$ with $x>3 m$, and let $y$ be the smallest element of $S$ larger than $x$. If $y > 2x$, then $y-x$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ not including $x$ in $k$ ways. If $y \in S$, then $y$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ in at least $k+1$ ways, a contradiction. Suppose now that $y \leq x+m$. We consider $z \in (2x-m, 2x)$. Similarly as before, $z-x$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ not including $x$ or $y$ in $k$ ways. If $y \in S$, then since $m < 2x - y$, $z$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ in at least $k+1$ ways, a contradiction.

From the Lemma, we have that $S=T \cup U$, where $T$ is finite and $U=\{x, 2x, 4x, 8x, \ldots\}$ for some positive integer $x$. Let $y$ be any positive integer greater than $s(T)$. For any subset $T^{\prime} \subseteq T$, if $y-s\left(T^{\prime}\right) \equiv 0 \pmod{x}$, then $y-s\left(T^{\prime}\right)$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $U$ in a unique way; otherwise $y-s\left(T^{\prime}\right)$ cannot be written as a sum of distinct elements of $U$. Hence the number of ways to write $y$ as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ is equal to the number of subsets $T^{\prime} \subseteq T$ such that $s\left(T^{\prime}\right) \equiv y \pmod{x}$. Since this holds for all $y$, for any $0 \leq a \leq x-1$ there are exactly $k$ subsets $T^{\prime} \subseteq T$ such that $s\left(T^{\prime}\right) \equiv a \pmod{x}$. This means that there are $kx$ subsets of $T$ in total. But the number of subsets of $T$ is a power of 2, and therefore $k$ is a power of 2, as claimed.

|

k=2^{a}

|

Combinatorics

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 874

|

Let $n \geq 3$ be a fixed integer. The number 1 is written $n$ times on a blackboard. Below the blackboard, there are two buckets that are initially empty. A move consists of erasing two of the numbers $a$ and $b$, replacing them with the numbers 1 and $a+b$, then adding one stone to the first bucket and $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$ stones to the second bucket. After some finite number of moves, there are $s$ stones in the first bucket and $t$ stones in the second bucket, where $s$ and $t$ are positive integers. Find all possible values of the ratio $\frac{t}{s}$.

|

The answer is the set of all rational numbers in the interval $[1, n-1)$. First, we show that no other numbers are possible. Clearly the ratio is at least 1, since for every move, at least one stone is added to the second bucket. Note that the number $s$ of stones in the first bucket is always equal to $p-n$, where $p$ is the sum of the numbers on the blackboard. We will assume that the numbers are written in a row, and whenever two numbers $a$ and $b$ are erased, $a+b$ is written in the place of the number on the right. Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be the numbers on the blackboard from left to right, and let

$$

q=0 \cdot a_{1}+1 \cdot a_{2}+\cdots+(n-1) a_{n}

$$

Since each number $a_{i}$ is at least 1, we always have

$$

q \leq(n-1) p-(1+\cdots+(n-1))=(n-1) p-\frac{n(n-1)}{2}=(n-1) s+\frac{n(n-1)}{2}

$$

Also, if a move changes $a_{i}$ and $a_{j}$ with $i2$. Call the algorithm which creates this situation using $n-1$ numbers algorithm $A$. Then to reach the situation for size $n$, we apply algorithm $A$, to create the number $a^{n-2}$. Next, apply algorithm $A$ again and then add the two large numbers, repeat until we get the number $a^{n-1}$. Then algorithm $A$ was applied $a$ times and the two larger numbers were added $a-1$ times. Each time the two larger numbers are added, $t$ increases by $a^{n-2}$ and each time algorithm $A$ is applied, $t$ increases by $a^{n-3}(a-1)(n-2)$. Hence, the final value of $t$ is

$$

t=(a-1) a^{n-2}+a \cdot a^{n-3}(a-1)(n-2)=a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)

$$

This completes the induction.

Now we can choose 1 and the large number $b$ times for any positive integer $b$, and this will add $b$ stones to each bucket. At this point we have

$$

\frac{t}{s}=\frac{a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)+b}{a^{n-1}-1+b}

$$

So we just need to show that for any rational number $\frac{p}{q} \in(1, n-1)$, there exist positive integers $a$ and $b$ such that

$$

\frac{p}{q}=\frac{a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)+b}{a^{n-1}-1+b}

$$

Rearranging, we see that this happens if and only if

$$

b=\frac{q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p\left(a^{n-1}-1\right)}{p-q} .

$$

If we choose $a \equiv 1(\bmod p-q)$, then this will be an integer, so we just need to check that the numerator is positive for sufficiently large $a$.

$$

\begin{aligned}

q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p\left(a^{n-1}-1\right) & >q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p a^{n-1} \\

& =a^{n-2}(a(q(n-1)-p)-(n-1))

\end{aligned}

$$

which is positive for sufficiently large $a$ since $q(n-1)-p>0$.

Alternative solution for the upper bound. Rather than starting with $n$ occurrences of 1, we may start with infinitely many 1s, but we are restricted to having at most $n-1$ numbers which are not equal to 1 on the board at any time. It is easy to see that this does not change the problem. Note also that we can ignore the 1 we write on the board each move, so the allowed move is to rub off two numbers and write their sum. We define the width and score of a number on the board as follows. Colour that number red, then reverse every move up to that point all the way back to the situation when the numbers are all 1s. Whenever a red number is split, colour the two replacement numbers red. The width of the original number is equal to the maximum number of red integers greater than 1 which appear on the board at the same time. The score of the number is the number of stones which were removed from the second bucket during these splits. Then clearly the width of any number is at most $n-1$. Also, $t$ is equal to the sum of the scores of the final numbers. We claim that if a number $p>1$ has a width of at most $w$, then its score is at most $(p-1) w$. We will prove this by strong induction on $p$. If $p=1$, then clearly $p$ has a score of 0, so the claim is true. If $p>1$, then $p$ was formed by adding two smaller numbers $a$ and $b$. Clearly $a$ and $b$ both have widths of at most $w$. Moreover, if $a$ has a width of $w$, then at some point in the reversed process there will be $w$ numbers in the set $\{2,3,4, \ldots\}$ that have split from $a$, and hence there can be no such numbers at this point which have split from $b$. Between this point and the final situation, there must always be at least one number in the set $\{2,3,4, \ldots\}$ that split from $a$, so the width of $b$ is at most $w-1$. Therefore, $a$ and $b$ cannot both have widths of $w$, so without loss of generality, $a$ has width at most $w$ and $b$ has width at most $w-1$. Then by the inductive hypothesis, $a$ has score at most $(a-1) w$ and $b$ has score at most $(b-1)(w-1)$. Hence, the score of $p$ is at most

$$

\begin{aligned}

(a-1) w+(b-1)(w-1)+\operatorname{gcd}(a, b) & \leq(a-1) w+(b-1)(w-1)+b \\

& =(p-1) w+1-w \\

& \leq(p-1) w .

\end{aligned}

$$

This completes the induction.

Now, since each number $p$ in the final configuration has width at most $(n-1)$, it has score less than $(n-1)(p-1)$. Hence the number $t$ of stones in the second bucket is less than the sum over the values of $(n-1)(p-1)$, and $s$ is equal to the sum of the the values of $(p-1)$. Therefore, $\frac{t}{s}<n-1$.

|

\frac{t}{s} \in [1, n-1)

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,634

|

Find all pairs $(a, b)$ of positive integers such that $a^{3}$ is a multiple of $b^{2}$ and $b-1$ is a multiple of $a-1$. Note: An integer $n$ is said to be a multiple of an integer $m$ if there is an integer $k$ such that $n=k m$.

|

.1

By inspection, we see that the pairs $(a, b)$ with $a=b$ are solutions, and so too are the pairs $(a, 1)$. We will see that these are the only solutions.

- Case 1. Consider the case $b<a$. Since $b-1$ is a multiple of $a-1$, it follows that $b=1$. This yields the second set of solutions described above.

- Case 2. This leaves the case $b \geq a$. Since the positive integer $a^{3}$ is a multiple of $b^{2}$, there is a positive integer $c$ such that $a^{3}=b^{2} c$.

Note that $a \equiv b \equiv 1$ modulo $a-1$. So we have

$$

1 \equiv a^{3}=b^{2} c \equiv c \quad(\bmod a-1) .

$$

If $c<a$, then we must have $c=1$, hence, $a^{3}=b^{2}$. So there is a positive integer $d$ such that $a=d^{2}$ and $b=d^{3}$. Now $a-1 \mid b-1$ yields $d^{2}-1 \mid d^{3}-1$. This implies that $d+1 \mid d(d+1)+1$, which is impossible.

If $c \geq a$, then $b^{2} c \geq b^{2} a \geq a^{3}=b^{2} c$. So there's equality throughout, implying $a=c=b$. This yields the first set of solutions described above.

Therefore, the solutions described above are the only solutions.

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 366

|

Find all positive integers $k<202$ for which there exists a positive integer $n$ such that

$$

\left\{\frac{n}{202}\right\}+\left\{\frac{2 n}{202}\right\}+\cdots+\left\{\frac{k n}{202}\right\}=\frac{k}{2}

$$

where $\{x\}$ denote the fractional part of $x$.

Note: $\{x\}$ denotes the real number $k$ with $0 \leq k<1$ such that $x-k$ is an integer.

|

Denote the equation in the problem statement as $\left(^{*}\right)$, and note that it is equivalent to the condition that the average of the remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 is 101. Since $\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$ is invariant in each residue class modulo 202 for each $1 \leq i \leq k$, it suffices to consider $0 \leq n < 202$.

If $n=0$, so is $\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$, meaning that $(*)$ does not hold for any $k$. If $n=101$, then it can be checked that $\left(^{*}\right)$ is satisfied if and only if $k=1$. From now on, we will assume that $101 \nmid n$.

For each $1 \leq i \leq k$, let $a_{i}=\left\lfloor\frac{i n}{202}\right\rfloor=\frac{i n}{202}-\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$. Rewriting $\left(^{*}\right)$ and multiplying the equation by 202, we find that

$$

n(1+2+\ldots+k)-202\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{k}\right)=101 k

$$

Equivalently, letting $z=a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{k}$,

$$

n k(k+1)-404 z=202 k

$$

Since $n$ is not divisible by 101, which is prime, it follows that $101 \mid k(k+1)$. In particular, $101 \mid k$ or $101 \mid k+1$. This means that $k \in\{100,101,201\}$. We claim that all these values of $k$ work.

- If $k=201$, we may choose $n=1$. The remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 are 1, 2, ..., 201, which have an average of 101.

- If $k=100$, we may choose $n=2$. The remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 are 2, 4, ..., 200, which have an average of 101.

- If $k=101$, we may choose $n=51$. To see this, note that the first four remainders are $51, 102, 153$, 2, which have an average of 77. The next four remainders $(53, 104, 155, 4)$ are shifted upwards from the first four remainders by 2 each, and so on, until the 25th set of the remainders (99, $150, 201, 50$) which have an average of 125. Hence, the first 100 remainders have an average of $\frac{77+125}{2}=101$. The 101th remainder is also 101, meaning that the average of all 101 remainders is 101.

In conclusion, all values $k \in\{1, 100, 101, 201\}$ satisfy the initial condition.

|

1, 100, 101, 201

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 825

|

Let $c$ be a positive integer. The sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}, \ldots$ is defined by $a_{1}=c$, and $a_{n+1}=a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+c^{3}$, for every positive integer $n$. Find all values of $c$ for which there exist some integers $k \geq 1$ and $m \geq 2$, such that $a_{k}^{2}+c^{3}$ is the $m^{\text {th }}$ power of some positive integer.

|

First, notice:

$$

a_{n+1}^{2}+c^{3}=\left(a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+c^{3}\right)^{2}+c^{3}=\left(a_{n}^{2}+c^{3}\right)\left(a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+1+c^{3}\right)

$$

We first prove that $a_{n}^{2}+c^{3}$ and $a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+1+c^{3}$ are coprime.

We prove by induction that $4 c^{3}+1$ is coprime with $2 a_{n}+1$, for every $n \geq 1$.

Let $n=1$ and $p$ be a prime divisor of $4 c^{3}+1$ and $2 a_{1}+1=2 c+1$. Then $p$ divides $2\left(4 c^{3}+1\right)=(2 c+1)\left(4 c^{2}-2 c+1\right)+1$, hence $p$ divides 1, a contradiction. Assume now that $\left(4 c^{3}+1,2 a_{n}+1\right)=1$ for some $n \geq 1$ and the prime $p$ divides $4 c^{3}+1$ and $2 a_{n+1}+1$. Then $p$ divides $4 a_{n+1}+2=\left(2 a_{n}+1\right)^{2}+4 c^{3}+1$, which gives a contradiction.

Assume that for some $n \geq 1$ the number

$$

a_{n+1}^{2}+c^{3}=\left(a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+c^{3}\right)^{2}+c^{3}=\left(a_{n}^{2}+c^{3}\right)\left(a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+1+c^{3}\right)

$$

is a power. Since $a_{n}^{2}+c^{3}$ and $a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+1+c^{3}$ are coprime, then $a_{n}^{2}+c^{3}$ is a power as well.

The same argument can be further applied giving that $a_{1}^{2}+c^{3}=c^{2}+c^{3}=c^{2}(c+1)$ is a power.

If $a^{2}(a+1)=t^{m}$ with odd $m \geq 3$, then $a=t_{1}^{m}$ and $a+1=t_{2}^{m}$, which is impossible. If $a^{2}(a+1)=t^{2 m_{1}}$ with $m_{1} \geq 2$, then $a=t_{1}^{m_{1}}$ and $a+1=t_{2}^{m_{1}}$, which is impossible.

Therefore $a^{2}(a+1)=t^{2}$ whence we obtain the solutions $a=s^{2}-1, s \geq 2, s \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

c=s^{2}-1, s \geq 2, s \in \mathbb{N}

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 736

|

\quad$ Let $\mathbb{Z}^{+}$ be the set of positive integers. Find all functions $f: \mathbb{Z}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}^{+}$ such that the following conditions both hold:

(i) $f(n!)=f(n)!$ for every positive integer $n$,

(ii) $m-n$ divides $f(m)-f(n)$ whenever $m$ and $n$ are different positive integers.

|

There are three such functions: the constant functions 1, 2 and the identity function $\mathrm{id}_{\mathbf{Z}^{+}}$. These functions clearly satisfy the conditions in the hypothesis. Let us prove that there are only ones.

Consider such a function $f$ and suppose that it has a fixed point $a \geq 3$, that is $f(a)=a$. Then $a!,(a!)!, \cdots$ are all fixed points of $f$, hence the function $f$ has a strictly increasing sequence $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{k}<\cdots$ of fixed points. For a positive integer $n$, $a_{k}-n$ divides $a_{k}-f(n)=$ $f\left(a_{k}\right)-f(n)$ for every $k \in \mathbf{Z}^{+}$. Also $a_{k}-n$ divides $a_{k}-n$, so it divides $a_{k}-f(n)-\left(a_{k}-n\right)=$ $n-f(n)$. This is possible only if $f(n)=n$, hence in this case we get $f=\mathrm{id}_{\mathbf{Z}^{+}}$.

Now suppose that $f$ has no fixed points greater than 2. Let $p \geq 5$ be a prime and notice that by Wilson's Theorem we have $(p-2)!\equiv 1(\bmod p)$. Therefore $p$ divides $(p-2)!-1$. But $(p-2)!-1$ divides $f((p-2)!)-f(1)$, hence $p$ divides $f((p-2)!)-f(1)=(f(p-2))!-f(1)$. Clearly we have $f(1)=1$ or $f(1)=2$. As $p \geq 5$, the fact that $p$ divides $(f(p-2))!-f(1)$ implies that $f(p-2)<p$. It is easy to check, again by Wilson's Theorem, that $p$ does not divide $(p-1)!-1$ and $(p-1)!-2$, hence we deduce that $f(p-2) \leq p-2$. On the other hand, $p-3=(p-2)-1$ divides $f(p-2)-f(1) \leq(p-2)-1$. Thus either $f(p-2)=f(1)$ or $f(p-2)=p-2$. As $p-2 \geq 3$, the last case is excluded, since the function $f$ has no fixed points greater than 2. It follows $f(p-2)=f(1)$ and this property holds for all primes $p \geq 5$. Taking $n$ any positive integer, we deduce that $p-2-n$ divides $f(p-2)-f(n)=f(1)-f(n)$ for all primes $p \geq 5$. Thus $f(n)=f(1)$, hence $f$ is the constant function 1 or 2.

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 684

|

Determine all positive integers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

x^{5}+4^{y}=2013^{z}

$$

|

Reducing modulo 11 yields \( x^{5} + 4^{y} \equiv 0 \pmod{11} \), where \( x^{5} \equiv \pm 1 \pmod{11} \), so we also have \( 4^{y} \equiv \pm 1 \pmod{11} \). The congruence \( 4^{y} \equiv -1 \pmod{11} \) does not hold for any \( y \), whereas \( 4^{y} \equiv 1 \pmod{11} \) holds if and only if \( 5 \mid y \).

Setting \( t = 4^{y / 5} \), the equation becomes \( x^{5} + t^{5} = A \cdot B = 2013^{z} \), where \( (x, t) = 1 \) and \( A = x + t \), \( B = x^{4} - x^{3} t + x^{2} t^{2} - x t^{3} + t^{4} \). Furthermore, from \( B = A \left( x^{3} - 2 x^{2} t + 3 x t^{2} - 4 t^{3} \right) + 5 t^{4} \) we deduce \( (A, B) = (A, 5 t^{4}) \mid 5 \), but \( 5 \nmid 2013^{z} \), so we must have \( (A, B) = 1 \). Therefore \( A = a^{z} \) and \( B = b^{z} \) for some positive integers \( a \) and \( b \) with \( a \cdot b = 2013 \).

On the other hand, from \( \frac{1}{16} A^{4} \leq B \leq A^{4} \) (which is a simple consequence of the mean inequality) we obtain \( \frac{1}{16} a^{4} \leq b \leq a^{4} \), i.e. \( \frac{1}{16} a^{5} \leq a b = 2013 \leq a^{5} \). Therefore \( 5 \leq a \leq 8 \), which is impossible because 2013 has no divisors in the interval [5,8].

|

not found

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 537

|

Let $S$ be the set of positive real numbers. Find all functions $f: S^{3} \rightarrow S$ such that, for all positive real numbers $x, y, z$ and $k$, the following three conditions are satisfied:

(i) $x f(x, y, z)=z f(z, y, x)$;

(ii) $f\left(x, k y, k^{2} z\right)=k f(x, y, z)$;

(iii) $f(1, k, k+1)=k+1$.

(United Kingdom)

|

It follows from the properties of function $f$ that, for all $x, y, z, a, b>0$, $f\left(a^{2} x, a b y, b^{2} z\right)=b f\left(a^{2} x, a y, z\right)=b \cdot \frac{z}{a^{2} x} f\left(z, a y, a^{2} x\right)=\frac{b z}{a x} f(z, y, x)=\frac{b}{a} f(x, y, z)$.

We shall choose $a$ and $b$ in such a way that the triple $\left(a^{2} x, a b y, b^{2} z\right)$ is of the form $(1, k, k+1)$ for some $k$ : namely, we take $a=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}$ and $b$ satisfying $b^{2} z-a b y=1$, which upon solving the quadratic equation yields $b=\frac{y+\sqrt{y^{2}+4 x z}}{2 z \sqrt{x}}$ and $k=\frac{y\left(y+\sqrt{y^{2}+4 x z}\right)}{2 x z}$. Now we easily obtain

$$

f(x, y, z)=\frac{a}{b} f\left(a^{2} x, a b y, b^{2} z\right)=\frac{a}{b} f(1, k, k+1)=\frac{a}{b}(k+1)=\frac{y+\sqrt{y^{2}+4 x z}}{2 x} .

$$

It is directly verified that $f$ satisfies the problem conditions.

|

\frac{y+\sqrt{y^{2}+4 x z}}{2 x}

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 385

|

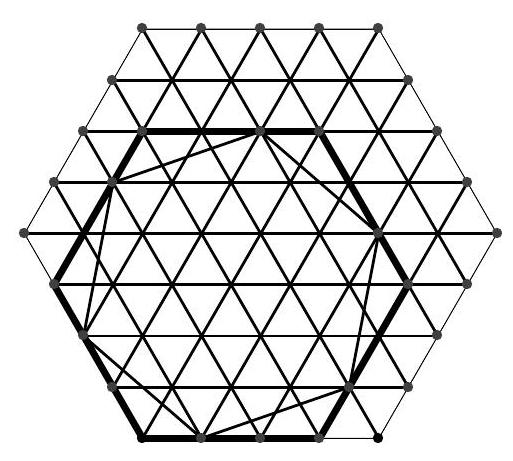

Let $n$ be a positive integer. A regular hexagon with side length $n$ is divided into equilateral triangles with side length 1 by lines parallel to its sides.

Find the number of regular hexagons all of whose vertices are among the vertices of the equilateral triangles.

|

By a lattice hexagon we will mean a regular hexagon whose sides run along edges of the lattice. Given any regular hexagon $H$, we construct a lattice hexagon whose edges pass through the vertices of $H$, as shown in the figure, which we will call the enveloping lattice hexagon of $H$. Given a lattice hexagon $G$ of side length $m$, the number of regular hexagons whose enveloping lattice hexagon is $G$ is exactly $m$.

Yet also there are precisely $3(n-m)(n-m+1)+1$ lattice hexagons of side length $m$ in our lattice: they are those with centres lying at most $n-m$ steps from the centre of the lattice. In particular, the total number of regular hexagons equals

$N=\sum_{m=1}^{n}(3(n-m)(n-m+1)+1) m=\left(3 n^{2}+3 n\right) \sum_{m=1}^{n} m-3(2 m+1) \sum_{m=1}^{n} m^{2}+3 \sum_{m=1}^{n} m^{3}$.

Since $\sum_{m=1}^{n} m=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}, \sum_{m=1}^{n} m^{2}=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6}$ and $\sum_{m=1}^{n} m^{3}=\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)^{2}$ it is easily checked that $N=\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)^{2}$.

|

\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)^{2}

|

Combinatorics

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 436

|

Find all injective functions \( f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \) such that for every real number \( x \) and every positive integer \( n \),

\[

\left|\sum_{i=1}^{n} i(f(x+i+1)-f(f(x+i)))\right|<2016

\]

|

From the condition of the problem we get

$$

\left|\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} i(f(x+i+1)-f(f(x+i)))\right|<2016

$$

Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

& |n(f(x+n+1)-f(f(x+n)))| \\

= & \left|\sum_{i=1}^{n} i(f(x+i+1)-f(f(x+i)))-\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} i(f(x+i+1)-f(f(x+i)))\right| \\

< & 2 \cdot 2016=4032

\end{aligned}

$$

implying

$$

|f(x+n+1)-f(f(x+n))|<\frac{4032}{n}

$$

for every real number $x$ and every positive integer $n$.

Let $y \in \mathbb{R}$ be arbitrary. Then there exists $x$ such that $y=x+n$. We obtain

$$

|f(y+1)-f(f(y))|<\frac{4032}{n}

$$

for every real number $y$ and every positive integer $n$. The last inequality holds for every positive integer $n$ from where $f(y+1)=f(f(y))$ for every $y \in \mathbb{R}$ and since the function $f$ is an injection, then $f(y)=y+1$. The function $f(y)=y+1$ satisfies the required condition.

|

f(y)=y+1

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 340

|

Find all ordered pairs $(x, y)$ of positive integers such that:

$$

x^{3}+y^{3}=x^{2}+42 x y+y^{2} \text{.}

$$

|

Possible initial thoughts about this equation might include:

(i) I can factorise the sum of cubes on the left.

(ii) How can I use the 42?

(iii) The left is cubic and the right is quadratic, so if \(x\) or \(y\) is very large there will be no solutions.

The first two might lead us to rewrite the equation as \((x+y)\left(x^{2}-x y+y^{2}\right)=x^{2}-x y+y^{2}+43 x y\). The number \(43=42+1\) is prime which is good news since we have \((x+y-1)\left(x^{2}-x y+y^{2}\right)=43 x y\).

Now we can employ some wishful thinking: if \(x\) and \(y\) happen to be coprime, then \(\left(x^{2}-x y+y^{2}\right)\) has no factors in common with \(x\) or \(y\) so it must divide 43. This feels like a significant step except for the fact that \(x\) and \(y\) may not be coprime.

This suggests writing \(x=d X\) and \(y=d Y\) where \(d\) is the highest common factor of \(x\) and \(y\).

We end up with \((d X+d Y-1)\left(X^{2}-X Y+Y^{2}\right)=43 X Y\) so \(X^{2}-X Y+Y^{2}\) equals 1 or 43.

The first of these readily gives \(X=Y=1\). A neat way to deal with the second is to assume \(Y \leq X\) so \(43=X^{2}-X Y+Y^{2} \geq Y^{2}\). This gives six cases for \(Y\) which can be checked in turn. Alternatively you can solve \(X^{2}-X Y+Y^{2}=43\) for \(X\) and fuss about the discriminant.

In the end the only solutions turn out to be \((x, y)=(22,22),(1,7)\) or \((7,1)\).

Another reasonable initial plan is to bound \(x+y\) (using observation (iii) above) and then use modular arithmetic to eliminate cases until only the correct solutions remain. Working modulo 7 is particularly appealing since \(7 \mid 42\) and the only cubes modulo 7 are 0, 1, and -1.

We have \(x^{3}+y^{3}=(x+y)^{3}-3 x y(x+y)\) and also \(x^{2}+42 x y+y^{2}=(x+y)^{2}+40 x y\) so the equation becomes \((x+y)^{3}=(x+y)^{2}+x y(3 x y+40)\). Now using \(x y \leq\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}\) leads to \(x+y \leq 44\).

This leaves a mere 484 cases to check! The modulo 7 magic is not really enough to cut this down to an attractive number, and although the approach can obviously be made to work, to call it laborious is an understatement.

Other possible approaches, such as substituting \(u=x+y, v=x-y\), seem to lie somewhere between the two described above in terms of the amount of fortitude needed to pull them off.

|

(22,22),(1,7),(7,1)

|

Algebra

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 746

|

Let $\mathbb{N}$ be the set of positive integers. Find all functions $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}$ such that:

$$

n+f(m) \text { divides } f(n)+n f(m)

$$

|

The striking thing about this problem is that the relation concerns divisibility rather than equality. How can we exploit this? We are given that $n+f(m) \mid f(n)+n f(m)$ but we can certainly add or subtract multiples of the left hand side from the right hand side and preserve the divisibility. This leads to a key idea:

'Eliminate one of the variables from the right hand side.'

Clearly $n+f(m) \mid f(n)+n f(m)-n(n+f(m))$ so for any $n, m$ we have

$$

n+f(m) \mid f(n)-n^{2}

$$

This feels like a strong condition: if we fix $n$ and let $f(m)$ go to infinity, then $f(n)-n^{2}$ will have arbitrarily large factors, which implies it must be zero.

We must be careful: this argument is fine, so long as the function $f$ takes arbitrarily large values. (We also need to check that $f(n)=n^{2}$ satisfies the original statement which it does.)

We are left with the case where $f$ takes only finitely many values.

In this case $f$ must take the same value infinitely often, so it is natural to focus on an infinite set $S \subset \mathbb{N}$ such that $f(s)=k$ for all $s \in S$. If $n, m \in S$ then the original statement gives $n+k \mid k+n k$ where $k$ is fixed and $n$ can be as large as we like.

Now we recycle our key idea and eliminate $n$ from the right.

$n+k \mid k+n k-k(n+k)$ so $n+k \mid k-k^{2}$ for arbitrarily large $n$. This means that $k-k^{2}=0$ so $k=1$, since it must be positive.

At this point we suspect that $f(n)=1$ for all $n$ is the only bounded solution, so we pick some $t$ such that $f(t)=L>1$ and try to get a contradiction.

In the original statement we can set $m=t$ and get $n+L \mid f(n)+n L$. Eliminating $L$ from the right gives us nothing new, so how can we proceed? Well, we have an infinite set $S$ such that $f$ is constantly 1 on $S$ so we can take $n \in S$ to obtain $n+L \mid 1+n L$

Using our key idea one more time and eliminating $n$ from the right, we get $n+L \mid 1-L^{2}$ for arbitrarily large $n$ which is impossible if $L>1$.

A rather different solution can be found by playing around with small values of $m$ and $n$.

As before it helps to establish $(\star)$ but now $(n, m)=(1,1)$ gives $1+f(1) \mid f(1)-1$.

The left is bigger than the right, so the right must be zero $-f(1)=1$.

Now try $(n, m)=(2,1)$ and obtain $2+f(2) \mid f(2)-4$. Subtracting the left from the right gives $2+f(2) \mid-6$. Since $f(2) \in \mathbb{N}$ the left is a factor of -6 which is bigger than 2 . This gives $f(2)=1$ or $f(2)=4$.

In the first case we can plug this back into the original statement to get $2+f(m) \mid 1+2 f(m)$. Now taking two copies of the left away from the right we have $2+f(m) \mid-3$.

Thus $2+f(m)$ must a factor of -3 which is bigger than 2 , so $f(m)=1$ for any $m$.

Before proceeding with the case $f(2)=4$ we take another look at our strong result $(\star)$. Setting $n=m$ gives $n+f(n) \mid f(n)-n^{2}$ so taking $f(n)-n^{2}$ away from $n+f(n)$ shows that

$$

n+f(n) \mid n+n^{2}

$$

Let see if we can use $(\star)$ and $(\dagger)$ to pin down the value of $f(3)$, using $f(2)=4$.

From $(\star)$ we have $3+4 \mid f(3)-9$ and from $(\dagger)$ we have $3+f(3) \mid 12$. The second of these shows $f(3)$ is 1,3 or 9 , but 1 and 3 are too small to work in the first relation.

Similarly, setting $(n, m)=(4,3)$ in $(\star)$ gives $4+9 \mid f(4)-16$ while $n=4$ in $(\dagger)$ gives $4+f(4) \mid 20$. The latter shows $f(4) \leq 16$ so $13 \mid 16-f(4)$. The only possible multiples of 13 are 0 and 13 , of which only the first one works. Thus $f(4)=16$.

Now we are ready to try induction. Assume $f(n-1)=(n-1)^{2}$ and use $(\star)$ and $(\dagger)$ to obtain $n+(n-1)^{2} \mid f(n)-n^{2}$ and $n+f(n) \mid n+n^{2}$. The latter implies $f(n) \leq n^{2}$ so the former becomes $n^{2}-n+1 \mid n^{2}-f(n)$. If $f(n) \neq n^{2}$ then $n^{2}-f(n)=1 \times\left(n^{2}-n+1\right)$ since any other multiple would be too large. However, putting $f(n)=n-1$ into $n+f(n) \mid n+n^{2}$ implies $2 n-1 \mid n(1+n)$. This is a contradiction since $2 n-1$ is coprime to $n$ and clearly cannot divide $1+n$.

for all $m, n \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

f(n)=n^2 \text{ or } f(n)=1

|

Number Theory

|

math-word-problem

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

olympiads_ref

| false

| 1,386

|

There are $n>2$ students sitting at a round table. Initially each student has exactly one candy. At each step, each student chooses one of the following operations:

(a) Pass one candy to the student on their left or the student on their right.

(b) Divide all their candies into two, possibly empty, sets and pass one set to the student on their left and the other to the student on their right.

At each step the students perform their chosen operations simultaneously.

An arrangement of candies is legal if it can be obtained in a finite number of steps.

Find the number of legal arrangements.

(Two arrangements are different if there is a student who has different numbers of candies in each one.)

|

One possible initial reaction to this problem is that there is rather too much movement of caramels ${ }^{2}$ at each step to keep track of easily. This leads to the question: 'How little can I do in, say, two steps?' If every student passes all their caramels left on one step using (b), and all their caramels right on the next step, then no caramels move. (This is rather too little movement.) Let us see what a small change to this sequence can accomplish. We choose a student with at least one caramel. At the first step, she passes one caramel to the right and any others she has to the left. Every one else passes everything left. At the next step everybody passes everything right. The effect of this is that exactly one caramel has moved exactly two places to the right. Similarly, there is a double step which moves exactly one caramel two places to the left.

If we have not already done so, now is the time to start working through some small values of $n$.

The case $n=3$ yields a useful observation. Going two places (let's call this a double jump) to the left on a triangle is the same as going one place to the right. Indeed if $n$ is odd, say $2 k+1$, then $k$ double jumps to the left moves the caramel one place to the right and vice versa.

It is now clear that, if $n$ is odd, any arrangement of caramels is possible. We simply move them into position one at a time.

In the case $n=4$ it seems hard to get all the caramels into one place. Indeed, if we limit ourselves to double jumps, then we can only get $(1,1,1,1),(1,2,1,0),(2,2,0,0)$ and rotations of these arrangements. What can we say about these? Well it seems that students one and three always hold two candies between them. Having noticed this, it is not too hard to make a more general observation: if $n$ is even then a double jump cannot change the total number of caramels held by the odd numbered students. However, double jumps are not the only moves available to us. For example, it is possible to go from $(2,2,0,0)$ to $(3,1,0,0)$. A double jump now gives $(2,1,1,0)$ as well.